Scotland, for a change Love the first Love the second Sooty A funny-looking dog A boring poem

Top

Bunbeg, Co. Donegal, Ireland.

Scotland, For A Change

A sandy beach was the one essential ingredient in our family holidays and Ireland is littered with them. Beaches, beaches everywhere, and almost all deserted. So many in fact, that in our family we had a saying “this is my beach – go and find your own”.

At first, with no car and not much money, our annual holiday was a bus trip to the seaside towns of Co. Down, where my sister and I would dig in the sand and splash in the sea to our hearts’ content while my mother read the newspaper and my father practised his golf shots. Later a Ford Anglia joined the family and the whole of Ireland was at our disposal.

To my parents, holidays meant escape from routine, noise and people, but especially people. Work colleagues, neighbours and friends were gladly left behind for two weeks every summer. As for my sister and I, we were probably lucky not to have been left behind too. I doubt if long hours in a small tin can with malignant children was what my parents had in mind when they bought the Anglia, but our live-in grandmother had wisely established her annual right to two child-free weeks, and each year she would book into a quiet guesthouse on the seafront in Donaghadee. We malignant children were mystified, unable to understand how Nana (who toiled endlessly for us all year childcaring, cooking, shopping and cleaning while her daughter worked full-time in the city) could possibly resist the charms of two weeks in our company, not to mention all the swimming, and the exciting beaches to dig in.

“Why doesn’t Nana want to come with us? Doesn’t she like Donegal?”

With no alternative, my parents would pack us into the back of the car with dolls, books and games, and set off for remote seaside locations in Co. Donegal or Co. Kerry. The car journeys felt never-ending. Never- ending to us once each other’s dolls had all been mutilated and we had run out of horrible things to say to each other; never-ending to our parents when they ran out of sarcasm, threats and horrible things to say back to us.

“No we aren’t nearly there yet Alison, we’ve only driven three miles” my mother would groan, and “I don’t care who dismembered whose doll, if you don’t shut up right now I’ll come back there and dismember the pair of you.” My mother’s voice of authority was effective; she was the only person I ever knew who could successfully command a cat to sit. As for my father’s threats to turn the car around and drive straight back home again if we didn’t shut up, we didn’t take them too seriously. We knew they both wanted to get there just as much as we did.

Each year we would rent farmhouses or solitary caravans as close to beaches as we could get without actually sleeping in the water. While my sister and I created architectural masterpieces of sandcastles with real moats and dungeons, my mother would drink tea and read the newspaper in peace. My father would hit golf balls or take us to the nearest shop to buy sketch books and coloured pencils. Many of my friends would have been mightily bored with this. Their parents would take them to caravan parks in fields outside busy seaside resorts. Their days would be spent on the pier or promenade, where there were dodgem cars, tattoo shops and amusement arcades. They would eat pink candy floss in Morelli’s Ice Cream Parlour on the sea front, or select a small patch of a crowded beach and set up windbreakers and folding tables.

When Beth and I were thirteen and eleven, my parents thought they would try something different, and announced that this year we would be going to Scotland for a change.

We took the ferry from Larne to Stranraer, drove through rain all the way to Ayr, and stayed in a Bed & Breakfast. The next morning Beth and I were thrilled to see that Ayr had a sandy beach, and didn’t see why we couldn’t just stay there for the whole holiday. My parents didn’t see why we should come all the way to Scotland to do something we could do in Donegal, and pushed us into the car and headed for Edinburgh where we visited the castle and watched the Edinburgh Military Tattoo. We had never seen so many people in kilts before. The bugles, bagpipes, drums and fanfares were a lot of fun once we got over our disappointment at learning that we weren’t going to see people getting tattooed, but all was eclipsed by the hope of spotting the ghost of a headless drummer or a spooky piper on the battlements.

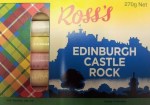

The next day, sadly lamenting the lack of visible ghosts in the castle, we looked at a lot of kilts in a lot of shop windows in the rain and bought boxes of soft, crumbly Edinburgh Rock.

Then we drove to Pitlochry and saw Blair Castle in the rain, missed Ben Nevis in the rain, and stayed the night at Fort William (in the rain).

The next day we set off for the fishing village of Mallaig on the west coast, where we had booked a harbour hotel for a week. We were still hoping to see the beautiful Scottish scenery we had heard so much about, and peered hopefully out of the car windows, but all we could see was a misty, grey rain and an endless, straight and narrow road with passing places. By the time we got to Mallaig, having missed most of the “high mountains, glens and deep lochs” mentioned in all the brochures, my father was frazzled with frustration at having to pull off the road every few hundred yards1, and we were all glaring poisonously at each other and wondering whether Mallaig might have a castle with dungeons. But at least it had stopped raining, and we did like the village, and the hotel. As for the harbour, it was pretty and smelt of fish; but then the same could have been said of my sister when she threw up her locally caught breakfast kippers the following day.

From Mallaig we took a day trip to the Isle of Skye, and begrudgingly declared it almost as beautiful as Ireland.

The sun had finally emerged and the sea was blue as we sailed off on the ferry. Beth stood at the rail looking at a couple who were watching the ferry leave.

“Look,” she said “They’re baffled.”

“Baffled? What are they baffled about?” I asked.

“They’re our foes and they’re baffled.” I looked at her, puzzled.

“Have you been eating kippers again?”

“No, stupid” and she burst into the Skye Boat Song. “Baffled our foes stand by the shore, follow they will not dare.”

“My favourite line is ‘Mull was astern, Rum on the port, Eigg on the starboard bow,’ I offered.

“Egg?” Now it was Beth’s turn to look puzzled.

“I suppose that’s what Bonnie Prince Charlie was eating. That’s what the song’s about you know.”

“Is that what it said in the book Mr. Boyd gave you?”

My school teacher had given me “Two in the Western Isles” by Mabel Esther Allan when I had my tonsils out in December. It had become our definitive reference manual on all things Scottish.

“I don’t know,” I thought, trying to remember if the song was in the book. “Tory and Jess go out in a boat to have an adventure, and they run out of petrol and get marooned on an island.” Beth looked up at the ferry bridge

“I wonder if this boat will run out of petrol?”

“Well you can always signal for help. In the book they take off their white blouses and use them to send S.O.S. signals,” I said helpfully.

The ferry managed to make it to and from Skye without running out of petrol. Which was just as well because we weren’t wearing blouses, but hand-knitted Fair Isle sweaters that our mother and grandmother had made. They weren’t white.

Although Skye was beautiful and we all loved the mountains, cliffs and heather, and even spotted a few eagles, the high point of the whole two weeks for Beth and I was when we found the long, sandy beaches of Morar, and we dug in and refused to be moved for several days. I don’t think our parents minded at all. My mother spread a rug on the beach, drank tea from a flask and read the newspaper, and my father hit golf balls.

1 Unlike Ireland, where remote roads are extremely twisty and have no passing places at all!

Love the First or The Hunting of the Snog Bit the First My name is not Carol though nonsense I write In a rhythm you might recognise, But as my First Romance I describe with delight Permit me to plagiarise. Bit the Second An innocent schoolgirl with dreams by the score (As in all the best Mills & Boon plots), I acquired a suspicion that schoolboys were more Than just gum-chewing horrors with spots. Bit the Third So picture the scene: I was young, I was green, With a gymslip conveniently matching, And a sporty young chap I did set out to trap By the means of a plan I was hatching. Bit the Fourth With his timetable handy my ways were discreet - I arranged to be always around. Nine times every day on the stairs we would meet And I'd drop all my books on the ground. Bit the Fifth In despair and defeat I would faint at his feet, But silent and strong he would stand. That could only imply that my hero was shy So a party I schemingly planned. Bit the Sixth With problems like parents and light bulbs removed, By my hero the bottle was spun - By some strange strategy it was pointing at me And we showed them all how it was done! Bit the Seventh Though so shy and so young, in a thick Mersey tongue He would say the occasional word. I go weak at the knees when I think of that squeeze - He's a sports teacher now I have heard. Bit the Eighth This romantic intrigue you may read with fatigue But to me it was better than Latin. There’s only one track that will bring it all back - Moody Blues singing “Nights in White Satin.” Alison Humphries 1984

Love the second

I am a Lewis Carroll fan;

(You may have guessed, perchance).

I've told thee everything I can

About my first romance.

But I was thinking of a plan

His poetry to equal,

By telling you the details of

My Second Love (the sequel).

One summer's evening long ago

My homework to evade,

I secretly embarked upon

A schoolgirl escapade.

I caught the 7 bus because

I'd missed the number 8,

The 10 mile detour meant that I

Was just a little late.

When I arrived of course I found

The party in full swing:

They'd painted all the light bulbs red

I couldn't see a thing!

But I was thinking of a plan

To light myself a candle,

And so thereby identify

Whoever I might handle.

But someone handled me instead!

I knew my luck was in

When I heard him make a sexy noise

That sounded like a grin.

I made romantic gestures which

I hoped he understood,

Like fluttering my eyelashes

As loudly as I could.

Then like the bashful girl I am,

Shy, modest and retiring,

I helped him go below the stairs

And check out all the wiring.

Of course there's plenty to relate

About what then occurred,

But just to keep thee guessing I

Will tell thee not a word.

In Monday's mathematics class

The whole affair he shouted,

I have to say, by light of day

My sanity I doubted.

His boasts I'm sure had more allure

Than logarithmic tables,

And yet I found this expose

A game I didn’t wish to play.

And so I planned a slight delay

In adding to my resume,

The details of the fateful day

I found myself in disarray

While contemplating cables.

And when from half a world away

That party I recall,

I wonder if I'm wiser now

And cannot say at all.

But if a certain song I hear

It all comes flooding back,

The painted light bulbs' scarlet glow,

The record player turned down low,

The smooching couples dancing slow,

Man of the World and I below

The stairs with Fleetwood Mac.

Alison Humphries 1984

+++++++++

Sooty by Alison

+++++++++

+++++++++

Which way did he go?

Local dog grows new head after visit to pulp mill